|

It is a

misconception that there truly is such a thing as a family coat of arms

or crest. In heraldry, a coat of arms was granted to an

individual, and it was not passed down. The sons would have each

applied for their own coats of arms when they earned that right through

service. Generally, out of respect for the father, the sons would

incorporate some aspect of the

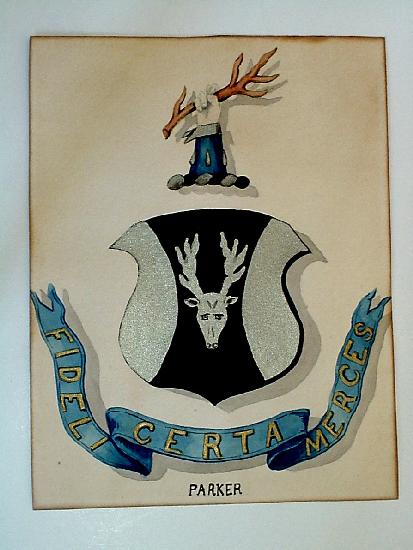

father's coat of arms into their own. The current genealogical use of crests and coats of arms is as a link to one of the family's early progenitors. In cases where there are several families with essentially the same surname, or several prominent branches of a family, it becomes difficult to determine which coat of arms is actually connected to an individual's ancestors. The Parkers are just such a case, as there are a number of registered coats of arms belonging to Parkers. Only a few of these various Parker families are actually related to one another. The Coat of Arms and Crest at left: A stag caboshed between two flaunches, argent. Crest: an arm erect vested azure, cuffed and slashed argent, grasping the attire of a stag, gules. Motto: Fideli Certa Merces (trans. - "The reward of the faithful is sure"). This Coat of Arms originated with the Parkers of Devonshire, from whom descend the Earls of Morley (initially titled Baron of Boringdon). According to the 1620 Visitation of Devon, this coat of arms had been in use by Parkers of Devonshire since 1547. The descendants of John Goldsbury Parker (1794 - 1875) and Ezra Aldis Parker (1795 - 1860), the eldest sons of Ezra Parker Jr of Winchester, New Hampshire, have used this coat of arms and crest for over 150 years. Edward Horatio Parker, one of the sons of John Goldsbury Parker, brought a copy of the Devonshire Parker Arms back with him after a visit to England in the late 1840s, claiming a connection to our family. Only recently has research for this compilation been able to establish that Edward Horatio Parker was wrong. This discovery by Edward Horatio Parker, and its subsequent acceptance by his brothers, sisters, and cousins, left a tantalizing and perplexing mystery that persisted for many decades. As far as has ever been recorded, no researcher has succeeded in tracing our immigrant Parker ancestor, John Parker of Cambridge Village (now Newton), Massachusetts, back to his English origins, a task made even more difficult by the near certainty that much of that John Parker's long-accepted early history in fact results from the combining of records of at least three other men named John Parker. The long-held Hingham myth of John's arrival seems to have originated from the coincidence that Thomas Hammond and Vincent Druce, two of the men John Parker was supposed to have moved from Hingham with, had settled in Hingham at about the same time as one of the John Parkers who actually did reside at Hingham, and had then purchased a piece of land in 1650 in Cambridge and another in Muddy River (near Brookline) adjoining land belonging to still another John Parker. Past researchers clearly made the erroneous assumption that the Parker who owned the land in Muddy River had to be the one who had been in Hingham, and that he was also the Parker who purchased land in Cambridge Village in 1650-51; early records plainly demonstrate that the John Parker of Muddy River and the John Parker of Hingham were two different individuals, and that neither was John Parker of Cambridge Village. How much was lost while generations of researchers tried to retrace a road from Cambridge Village to Hingham that our John Parker certainly never traveled? And yet, we had the puzzle of this coat of arms. Like all that have gone before, this compilation cannot trace John Parker of Cambridge Village to England. Yet somehow, Edward Horatio Parker's research into the family lineage led him to Devonshire. If it had been just chance that took him through North Moulton, where he had happened upon the ancient Parker home, it would seem doubtful Edward could have persuaded his relatives that they had any legitimate basis for adopting this coat of arms as their own, even though ultimately Edward was wrong. If he had been actively pursuing his research while in England, and had employed a professional genealogist with only the information generally available concerning John Parker of Cambridge Village, a scrupulous professional would have told him there was not enough evidence to launch a serious search. An unscrupulous professional genealogist, however, would likely have played the percentages and directed Edward to the north of England, from where the large majority of New England Parkers originate. The main Parker family of northern England has long had coats of arms featuring three leopard heads. In the early 1930's, research of Edward Carroll Parker, a grand-nephew of Edward Horatio Parker, made a connection to the Parkers of Devonshire at least seem possible, based on the will of Edmund Parker of North Moulton, Devonshire, who had married Anna (or Amy) Seymour. This Edmund Parker had a son named John who is recorded as being six years of age in 1620, indicating he was born about 1614 (Burke's Peerage claims John died in infancy, but the 1620 Visitation of Devon and the will of Edmund Parker prove otherwise). John Parker of Cambridge Village is recorded as being 71 years of age at his death in October of 1686, placing his birth about 1615. John of Devonshire is recorded in his father's will, dated 6 November 1642. Interestingly, John of Devonshire is the only one of Edmund's sons who receives no grant of land from his father's estate. John received only a bequest of 200 pounds, to be paid within one year of Edmund's death, and the forgiving of a 500 pound debt he owed his father. Edmund's will was proved by his eldest son, also named Edmund, on 21 November 1649. Edward Carroll Parker's research could find no subsequent record of John of Devonshire in England. Owing to his budgetary limitations, however, this research, which required the employing of a professional research agent in London, was limited to records available at the Prerogative Court of Canterbury and the Public Records Office. In Lincolnshire Pedigrees [Arthur Roland Maddison, ed.; London: The Harleian Society, 1904] a pedigree of the Southcote family appears on p. 914 of volume III, showing a "John Parker of Boringdon, co. Devon; aet. 6, 1620" who married a daughter (unnamed) of Thomas Southcote, originally of Buckland Toussaints, co. Devon, and later of Blyborough. This John Parker had a son named Edmund Southcote Parker, clearly named for John's father, who was born about 1651 (at which time John Parker of Cambridge Village is definitively established in Massachusetts). This Edmund received the Blyborough estate from his uncle, Sir John Southcote, and altered his own name to Southcote. Subsequent generations would be named as nn Parker Southcote. The fact that the John Parker who married the daughter of Thomas Southcote is listed being from Boringdon, and as aged 6 in 1620, seems to establish, if not with absolute certainty, then at least with a very high degree of probability, that he is the son of Edmund Parker and Anna Seymour. While the research of this compilation had previously supposed that the loan and subsequent posthumous grant from Edmund Parker, the father, was either to assist a younger son in starting a new life in North America, or to save a reckless spender from his creditors, and that the fact that John received no grant of land suggested either he had left England or was not considered financially responsible enough to be trusted with any part of the family estates, it now seems more likely the initial loan was to allow John to travel to the estate of his future in-laws in the appropriate style and dress, while the smaller amount of the subsequent bequest and the absence of a grant of land indicates that John had married well and by then had no need of either. With this determination, the theory of a Devonshire connection can all but certainly be laid to rest. It is still not clear just how Edward Horatio Parker came to his conclusion, and probably never will be. Given that the conclusion is now disproved, it seems likely he was either guessing or operating on faulty data, but this is nothing more than speculation, as Edward's papers did not survive and his family never recorded what his evidence was. If Edward was simply guessing, then he may have just happened across the Parker estate in North Moulton, sketched a copy of the coat of arms, and returned home with the readily available documentation that it was a valid coat of arms belonging to the Parker family which were now the Earls of Morley. How this draws a specific link to John Parker of Cambridge Village is completely unclear, and for someone who was conducting a study of the family history, should not have been anywhere near enough. A second possibility is that Edward Horatio Parker instead made an educated guess based on probabilities of where John of Cambridge Village likely came from. Unfortunately, since nothing has yet been found to indicate where John actually did come from, there is no means of accomplishing this without accepting the long-held but factually-deficient theory that John immigrated through Hingham. Hingham was founded in 1635, with a major portion of its first settlers coming from Norfolk, England. There is a suggestion that there were Parkers in Norfolk at that time who were an offshoot of the Devonshire Parkers. If Edward was able to establish a link between the Norfolk and Devonshire Parkers, he might have used this as his basis to hypothesize that these were the ancestors of John of Cambridge Village. The problem remains, however, that this theory depends on John Parker having immigrated through Hingham, which he clearly did not. A possible argument against this being Edward's working hypothesis is that Edward's sister, Jane Caroline Parker, the family historian of her generation, apparently did not accept the notion of John of Cambridge Village immigrating through Hingham. In a letter to her nephew about 1905, Caroline describes "the first John Parker" as "at Newton, 1650 - 1686", making no reference at all to Hingham. If Caroline and Edward had the same information, that would offer a good possibility that Edward did not accept the Hingham theory either. In any case, the question is largely moot, now that it is established that John Parker of Devonshire and John Parker of Cambridge Village could not have been the same man. Nonetheless, it remains an historical fact that the descendants of John Goldsbury Parker and Ezra Aldis Parker have adopted this coat of arms in good faith for over 150 years on the supposition that a connection might exist and was at least possible. To that extent, the Devonshire Parker arms are also an informally adopted part of the history of this Parker line, even if a genuine connection now clearly does not exist. |

|||||

HOME

| "A Parker Family History: of

Parkers, Brents, Lysters, Mitchells, Shermans, and more." Copyright 2001-2010 by Charles Parker |